[From December 26, 2007]

The Judge shows the Artist's Sketch-Book

…he with camp stool and dripping umbrella slung on his shoulders, with broad slouch hat crushed down over his eyes, and a variegated panorama of the road along which he had passed painted by the weather upon his back--the artist, whose hands were filled with the mystic tin box; behold him! the envied cynosure of boyish eyes.

- Edward King, describing the artist James Wells Champney, who accompanied King on an expedition through the Southern Appalachians in 1873.

Artists have been looking at these mountains for a long, long time...

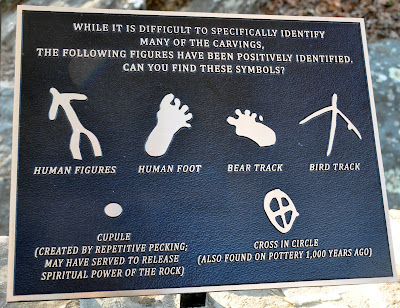

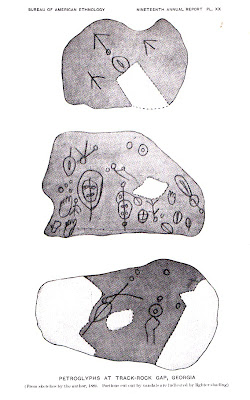

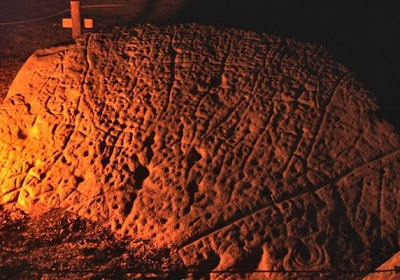

A thousand years ago they created the petroglyphs on Judaculla Rock.

A couple of centuries ago, naturalists like William Bartram sketched the plant life and other sights they encountered in these hills.

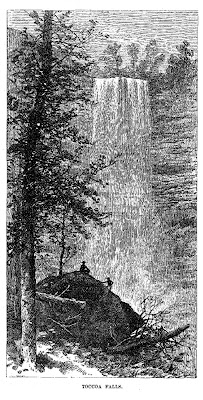

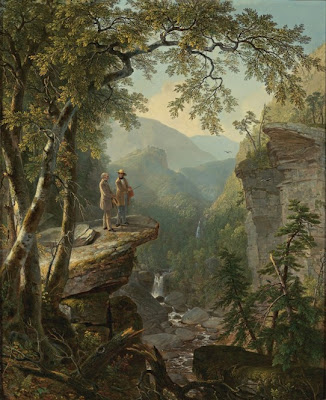

In the 1850s, William Frerichs explored the Blue Ridge and the Smokies to get inspiration for his majestic oil paintings "Tamahaka Falls" in Cherokee County, NC.

After the end of the Civil War, magazine publishers had an insatiable appetite for travel stories describing the people and scenery of the Southern Appalachians.

More than one scholar has opined on how these articles shaped and reinforced stereotypes about mountain people. But I’ve not seen much written about the artists who supplied the illustrations that accompanied the travel stories of the late nineteenth century.

Take for instance, James Wells Champney (1843-1903). He accompanied the writer Edward King on travels throughout the South and made more than 500 sketches during their journeys. The two traveled more than 25,000 miles together.

James Wells "Champ" Champney has been described as:

a prolific artist whose work was of high quality and broad scope. He was very successful as a oil painter of genre scenes, and later was perhaps the foremost pastelist of his day. A lecturer, illustrator, watercolorist and photographer, he was also one of the first Americans to grasp and utilize the spirit of impressionism.

Born in Boston, the artist studied drawing at Lowell Institute and took courses in anatomy from Oliver Wendell Holmes. Champney had already visited Europe for further studies and exhibited at the Paris Salon before he was commissioned by Scribner’s to illustrate the Edward King articles.

Afterwards, he returned to Europe and provided figure drawings of American life for the French magazine, D’Illustration. By 1876, he settled in Deerfield, Massachusetts where he taught art at Smith College.

J. Wells Champney married Elizabeth Williams (1850-1922) in May 1873, just prior to his visit to Western North Carolina. Elizabeth Champney herself began to publish short sketches, poems, books on art, and romantic travel stories, some of which were illustrated by her husband.

After Mr. Champney opened a studio in New York City in 1879, the couple divided their time between Deerfield and New York, and made frequent visits to Europe. Further, we read:

He was an early and avid amateur photographer, and also used the camera as an aid to his work. He was fond of books and the theatre, was a member of a dozen clubs and artists’ societies, and with Mrs. Champney entertained generously at their Fifth Avenue home and at Deerfield. "When they arrived, and Mr. Champney was seen on the street, the old town always seemed to come alive," wrote one villager.

Champney was in great demand as a lecturer, as suggested in December 18, 1894. New York Times article:

The members of Sorosis had a pleasant gathering in the parlors of Sherry’s yesterday afternoon, when J. Wells Champney told them many interesting things about pastels… The bright and luminous tints of the pastel, Mr. Champney said, are due to the fact that ‘the integrity of the molecule is intact,’ and that there is not ‘gumming together,’ as with paints… He humorously recommended the pastel as a valuable health thermometer, to be kept by every family, for if the pastel showed signs of succumbing to its one great enemy – dampness – the welfare of the household should be looked after.

An 1899 story described Champney’s presentation at the Carlisle Indian School:

On Tuesday evening, J. Wells Champney, the famous pastel artist of New York City, delivered a lecture before the Literary Societies and a large audience from town in Assembly Hall. The lecture was replete with wit and interesting anecdote. From the beginning lines of a straight-edged pig the artist with chalk and crayon led up to the graceful curves of a child's face, and on to the picturesque in landscape, giving scientific reasons for changes of lines, in a most attractive manner which could never tire the listener.

On May 1, 1903, Champney fell to his death. Champney had gone to the Camera Club of New York to make some photographic prints. As Champney got on the elevator, a piece of walnut furniture was too large to be carried in the car, so the operator had placed it on top, where it shifted and jammed the elevator between floors.

The headline of the New York Times article stated "His Death Was Due to His Hurry and Disregard of Warning." As reported by the Times:

Against the protests of the elevator boy, he attempted to swing himself to the floor below. He lost his hold on the car floor and fell down the shaft….

Mrs. Champney was notified by the police of her bereavement, and showed great fortitude after learning of her husband’s death. "We were very happy together," she said. "He was one of the most beautiful characters in the world and was always lovable. His life was just like his work."

So here’s to Champ, and his summer in the mountains 134 years ago, when he looked around Waynesville and Webster, Cullasaja Falls and Whiteside Mountain, and drew the world he saw.

---

Illustrations (From top)

1. From The Great South, "The Judge", a member of the travel party, shows Champney’s sketch book to a group of mountain folks, illustration by James Wells Champney.

2. Judaculla Rock by firelight

3. Morning Glory, by William Bartram

4. Falls of Tamahaka, oil on canvas, William Frerichs

5. James Wells Champney and daughter, Maria, ca. 1874

6. Elizabeth Champney

7. Feeding Chickens, oil on canvas, James Wells Champney

8. The Poppy Garden, James Wells Champney

9. Mount Pisgah from The Great South, illustration by James Wells Champney

239 of Champney’s sketches from The Great South trip are housed at the Lilly Library Manuscript Collection, Indiana University.

Finally, a passage from The Great South, in which Edward King describes their mode of travel:

It is sometimes said that Western North Carolina is shaped like a bow, of which the Blue Ridge would form the arc, and the Smoky mountains the string. Within this semicircle our little party, now and then increased by the advent of citizens of the various counties, who came to journey with us from point to point, traveled about 600 miles on horse-back, now sleeping at night in the lowly cabins, and sharing the rough fare of the mountaineers, now entering the towns and finding the mansions of the wealthier classes freely opened to us. Up at dawn, and away over hill and dale; now clambering miles among the forests to look at some new mine; now spurring our horses to reach shelter long after night had shrouded the roadways, we met with unvarying courtesy and unbounded welcome.

Addendum

If I ever write a book entitled "The Most Interesting People I Never Met," James Wells Champney will definitely merit a chapter.

His superb artistry is evident in several more of my favorite illustrations from The Great South, (and especially his depiction of Dry Falls, on the Cullasaja River):